You’ve probably been hearing more about license plate readers and Flock Safety over the last few months.

With resistance against authoritarian control growing, footage from cameras like these raise serious questions about mass surveillance and privacy.

Over the last few months, we’ve learned via reporting by 404 Media that Flock’s cameras, in particular, have been used to do a lot more than locate stolen cars and missing people.

They are also being used nationwide to monitor abortion care, surveil protests/demonstrations, and for immigration enforcement.

We took a deep dive into how these cameras work, why AI is supercharging the risks, and the current and proposed safety standards to protect our families from invasive surveillance tech.

Flock Safety in New Mexico

The Otero County Sheriff’s Office and Alamogordo police recently announced an agreement with Flock to “enhance safety.”

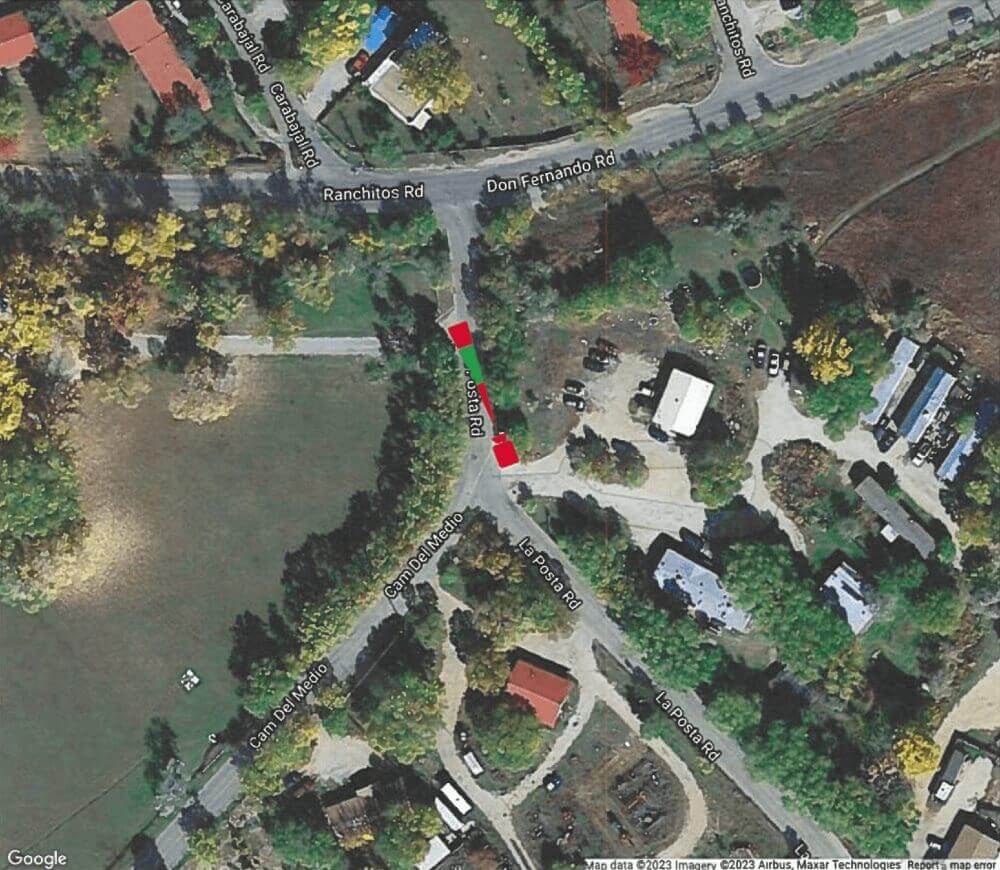

Bernalillo County started using Flock Safety and Axon, another provider, in 2024, according to Sheriff John Allen. Public records show that beginning in 2023, Taos also installed 18 of Flock’s license plate readers near the main plaza and along residential streets. That’s 18 cameras watching your daily life — without your consent.

Las Cruces, in particular, has embraced the company’s technology, installing a combination of up to 37 license plate readers and pan/tilt/zoom (PTZ) cameras, based on a review of public records. Those cameras can also be controlled remotely to follow people and vehicles and zoom in on faces and license plates in real time.

The history behind ALPRs and Flock Safety

Automated license plate readers are sometimes called ALPRs or just LPRs for short.

The base technology has been around for roughly 20-25 years, and privacy advocates have repeatedly raised concerns about the potential for misuse. For example, ACLU of New Mexico warned about sensitive information being captured and weaponized back in 2013.

Each device is mounted on a police car, road sign, or traffic light. As you drive by, it takes up to a dozen still images of your license plate, which is then added to a database that law enforcement can search.

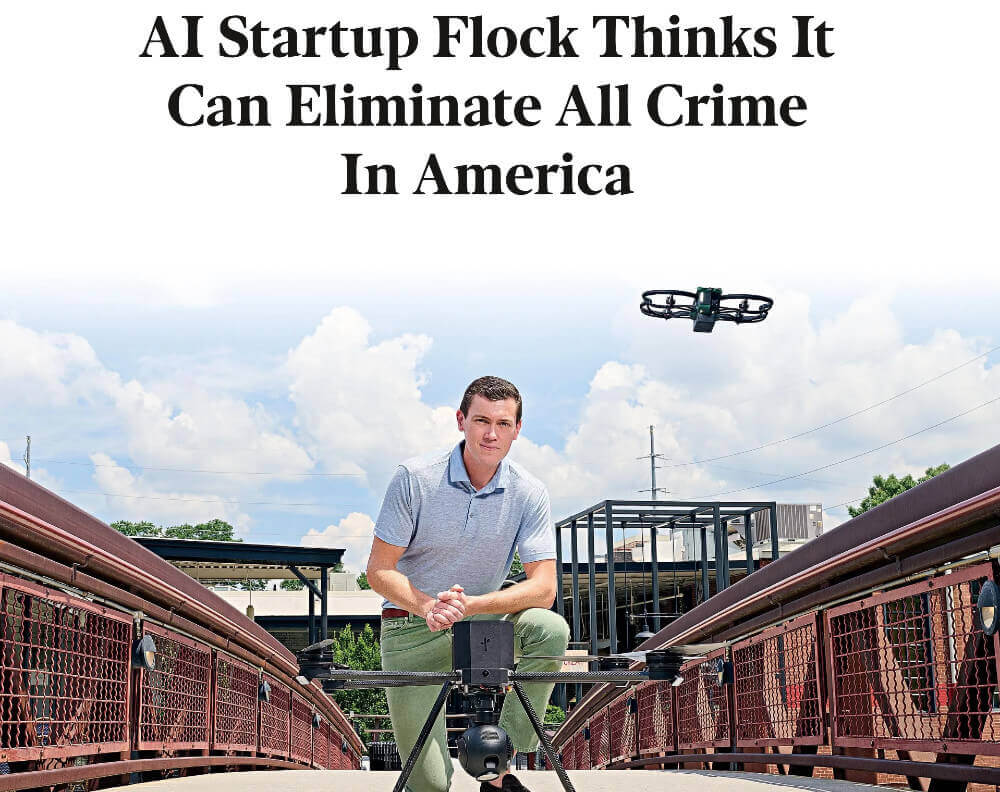

Founded in 2017, Flock started with an original product of automated license plate readers. But don’t let the name fool you. This isn’t just about catching stolen cars.

Flock’s newest camera product includes the pan, tilt, zoom (PTZ) feature. In recent years, the company has also connected multiple data sources to their Flock OS dashboard.

The Las Cruces contract mentions both the PTZ camera system as well as an integration with Peregrine, which uses machine learning and AI tools to analyze content in real-time.

Flock and its controversial CEO Garrett Langley are also known for praising AI tech and the use of broad surveillance as part of their goal of “preventing all crime in America.”

It’s also worth noting that Flock is a private company backed by venture capitalists by close to $950M. The common tech startup motto of “move fast, break things” surely applies here.

For example, in December 2025, a researcher found that video feeds from Flock’s AI-powered cameras were left exposed on the internet, accessible with no password or login. The footage included recordings of unattended children at a playground. And, completely unredacted Flock audit logs with millions of license plate searches were recently exposed to the public.

Far from creating safety, this kind of negligence puts communities at greater risk.

“Move fast, break things” is also a scary concept to introduce to local police, sheriffs, and state police, as well as federal authorities like the FBI and DHS/ICE, because it creates incentive to use our taxpayer money and resources to break the law and violate the US constitution.

An urgent situation

Flock, in particular, has aggressively expanded and marketed new AI tech and tools into their business model.

For example, when Las Cruces signed a contract in 2021, the company threw in a free “Raven audio detection,” a product that recently started listening for human voices. The city did not extend that option in a September 2024 renewal contract worth up to $737K.

In October, Amazon Ring also announced a partnership with both Flock and Axon to share Ring video camera footage with police. Combined with Amazon’s “familiar faces” AI recognition, this provokes disturbing, large scale concerns about mass surveillance. That means that your front door camera is now feeding data to the police.

In other words, this isn’t a distant, hypothetical risk. Over the last year, we’ve seen unsafe and invasive surveillance behavior occurring nationwide.

The surveillance net is also far from limited to law enforcement agencies or Ring cameras — Flock is rapidly expanding. We spoke with two separate people in Albuquerque’s Foothills and Northeast Heights neighborhoods who confirmed Flock was pitching the company’s HOA product with their homeowners association.

How to protect our privacy as New Mexicans

Flock’s questionable business practices have already prompted cities like Flagstaff, Eugene, and Cambridge to move quickly to revoke their contracts in recent months.

Given that Flock provided ICE and DHS with logins to search nationwide data — even in states like New York and Washington where local agencies had opted out — revoking contracts may be a wise move.

There are also some common sense protections that any state legislature, city, or county can put in place.

Put guardrails on data storage – one relatively easy safety measure would be to set standards for how long local agencies can save and store audio and camera footage.

For example, does the Albuquerque Police Department really need to store footage for a full year? Even Bernalillo County Sheriff John Allen has emphasized that 30 days is a reasonable period of time, and police always have the option to save specific footage to attach to an investigation.

Another option, which would take more work, would be to self host and manage data at the local level instead of relying on private companies who mine data and quietly change product features and access to pad their own profits.

Limit data access by outside agencies – in the recent legislative session, state lawmakers took a good step forward with SB 40 The Driver Privacy and Safety Act, which passed with strong bipartisan support and was signed into law by the governor.

The bill limits data sharing outside of the state and is aimed at preventing agencies like DHS, ICE, and Border Patrol from using camera data for increasingly reckless and dangerous immigration enforcement. It could also stop police from outside of New Mexico hunting someone down for accessing abortion or gender affirming healthcare.

Pass strong data protections for all residents – during the 2026 session lawmakers considered but did not pass NM CHISPA, a comprehensive privacy law that would give New Mexicans transparency, security, and control over their own information.

Given the increasing recognition that privacy is a basic human right, passing CHISPA would make it clear to private companies that our safety and well being is not for sale.

If you haven’t spoken with your state legislator, county commissioners, city councilor, school board member, etc. about this topic, take a moment to send them this story and let them know your concerns.

All of this surveillance is funded by our taxpayer resources so we deserve a say in what happens. Every New Mexican deserves both privacy and the assurance that their personal information will be treated with respect.

This article was originally published on January 14, 2026 and updated on March 11, 2026.